Hey Barnwell Community,

I wanted to share some work that hits on a key theme of ours at Barnwell Bio: early detection.

Our long running hypothesis (based on our previous work on Covid), has been that if farms do surveillance on an ongoing basis, they can detect and treat problems sooner than they would otherwise.

This is partially a function of biology - for some diseases there is a long pre-symptomatic period where the animals are shedding the pathogen but the animals appear healthy. And partially a function of proactiveness - routine monitoring, with the right technology, will help get ahead of things sooner.

We’re excited to share that this hypothesis seems to be bearing out, and I can point to an example from one of our incredible partners, Mississippi State University (MSU).

For some quick background, we got connected to MSU through our friends at AgLaunch. We are lucky to partner with Dr. Luis Muñoz and have found MSU to be the perfect place to do trial work, with both controlled research barns and commercial houses where they grow broilers for a large integrator. This allows us to examine the impact of our technology in a "real world" setting, generating better quality and more transferable insights to industry partners.

This past summer, we began implementing our technology and monitoring MSU’s two commercial barns weekly. Jake and I trained the team up on how to collect the samples, and collected the first samples ourselves!

The two barns are relatively healthy, though there were some historical differences in performance. Recently they have seen a few flocks with kinky back (also called spondylolisthesis - a spinal deformity in broiler chickens where the backbone curves or twists abnormally. Very easy to spot visually once it’s there!) - not outbreak level, but certainly was causing higher than normal mortality. There are a few causes of kinky back, but the most common being Enterococcus cecorum.

As we started monitoring the flock, we saw normal microbial development patterns around placement (lots of changes to the microbial community), and for the first few weeks as the birds settled in (the microbial ecosystem stabilized).

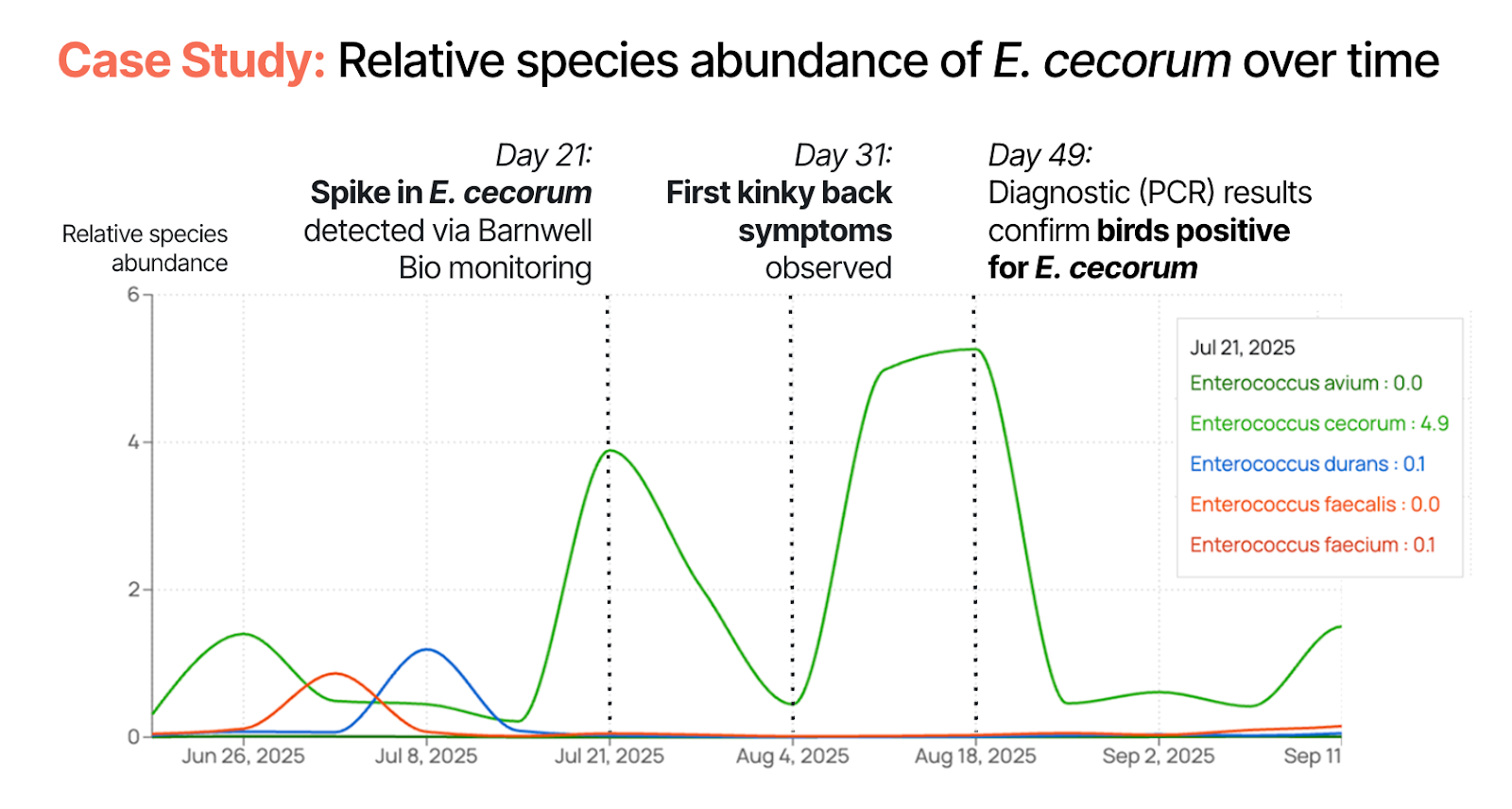

Then starting in week 3 (Day 21, see image below) we saw a notable increase in E. cecorum in our data. Yet, nothing highly unusual was reported. We flagged this to the MSU team, and soon after, they reported seeing multiple birds with paralysis and kinky back symptoms.

A snapshot of Barnwell Bio’s software dashboard, showing all species of Enterococcus we are monitoring.

MSU did some confirmatory PCR / 16S testing on individual birds showing symptoms. Around week 9 they got the results back confirming what we had seen in our data - the impacted birds tested positive for E. cecorum. (Though interestingly, not all of the birds with clear symptoms tested positive - this is a nugget for another time, but also a good example of why barn-level surveillance, versus testing individual animals, is critical!)

Because we were monitoring the barns on a regular basis, our data provided a weeks-long window of action to be able to intervene quickly and decisively, as compared to normal protocols. In this case, given how short broilers’ lifespans are, we’re really thinking about what happens with the next flock - what producers can do in between flocks with the litter, how producers should think about vaccinations, etc. However, for layers and breeders, who are on the farm much longer, early detection can allow farmers to intervene within the life of the flocks.

Through our partnership with MSU, this example demonstrates the value Barnwell Bio’s monitoring can provide. Our hope is that Barnwell Bio’s data can better prepare operators and veterinarians for animal health risks that may pop up. We’ll have more stories to share soon!

.webp)